学校は教育だけではない、重量なスキルを学ぶ場所!!

社会性、共感力、情緒 集団生活は多くを学ぶ場所。

そのことを実感したコロナ禍の今。

教育現場は、本当に大変な状況でしょう。しかし

そんな中でも光はある!!

皆で共有したい今日のVOAニュース。

パンデミックに重要な社会的、感情的スキルの教育

Teaching Social, Emotional Skills Critical in Pandemic

ブライアント・アテンシア氏にとっては、授業計画よりも生徒の社会的・情緒的な幸福が重要です。

コロナウイルスの流行は、彼が高校で教えているフィリピンのラグナ州の生徒とその家族に影響を与えています。生徒たちはまた、彼が通信教育への”巨大な調整”と呼ぶものに直面しているのです。

アテンシア氏はVOAに、健康危機が始まる前は、主に本から教えたり、教材のテストをしたりしていたと語っています。

「しかし今は、感情に触れ、生徒や保護者と触れあうようにしています。オンラインレッスンを受講している生徒さんがより快適に過ごせるような関係性を構築するように心がけています。」と語りました。

今、世界中の先生方がオンライン学習のために授業計画を修正しています。そのため、社会性と情動のスキル(SEL)を教えることは、彼らのTo Doリストの上位にはないかもしれません。しかし、一部の専門家は、これらのスキルがこれまで以上に重要であると言っています。

希望が浮かんでくる

クリスティーナ・チプリアーノ氏は、コネチカット州のイェール大学感情知能研究センターの研究責任者です。3月に学校が閉鎖された後、彼女は教師に宛てた公開書簡の中で、「今こそSELについて学んだことをすべて応用する必要があります。」と書いています。さらに彼女は、これらは”これからの数日間、数ヶ月間、感情のジェットコースターを管理するために私たちをサポートすることができます実際のスキル”であると付け加えています。

アテンシア氏は、教師のトレーニングをしたり、別の仕事で英語を教えたりしていますが、何が来てもいいように準備をしていました。5月には、SELとその使い方についてのオンライントレーニングを受けました。

高校生の授業が始まる1ヶ月前には、毎週のようにZoomビデオ会議を開きました。彼の目標は、生徒たちに遠隔学習に興味を持ってもらうことと、生徒たちのスキルとニーズを特定することでした。

ある会議では、アテンシア氏は生徒たちをオンラインの3つの別々の”部屋”に分け、創造的な活動をさせました。アテンシア氏は、学生たちが独立して、あるいはグループでどの程度の成果を上げているか、また、今後どの学生が最もサポートを必要としているかを確認したかったのです。

Collaborative for Academic, Social and Emotional Learning学術的・社会的・情動的学習のための共同研究会(CASEL)は、研究と研修を行う組織です。CASELは、社会性と情動のスキルを5つの分野に分けています。それは、自分の感情を認識してコントロールすること、前向き・肯定的な目標を設定して達成すること、他人に共感を示すこと、ポジティブな人間関係を発展させて維持すること、責任ある決断をすることです。

イェール大学のセンターの研究では、幸福感や好奇心のような感情が、注意を払い、学校での関わりを深める能力をサポートしていることがわかりました。しかし、不安や恐れのような感情は、特に長い期間にわたって、明確に考える能力を傷つけます。

アイリーン・ワッツさんは、このような生徒の不安を目の当たりにしてきました。

20年間の教師生活の中で、ホームレスや特別な教育を必要とする生徒など、様々な立場の生徒たちと一緒に働いてきました。また、米国に住むイラク人の子供たちにも教えた経験があります。

ワッツさんは、長年にわたり、授業の中に何らかの形でSELを取り入れてきたと言います。

昨年は、バージニア州マクリーンの学校で6年生を教えました。生徒の中にはイラクで生まれ、友人や家族が殺されるのを目の当たりにした生徒もいました。

ワッツさんは、彼女や他の教師が生徒の不安を軽減するための活動を組み込んだといいます。授業は”ブレーンブレイク”と呼ばれるもので、短いゲームをしたり、ダンスをしたりするために授業を中断することもありました。また、子供が不安を感じている場合は、誰かとパートナーを組むことで感情を落ち着かせることができます。

「私たちは、子供たちがストレスを感じていると、新しい情報を取り入れることができないことを発見しました。参加しないのです。」

アーカンソー州に拠点を置くワッツさんは、バージニア州にある米陸軍基地フォートベルボアで5年生を対象としたオンライン授業を始めたばかりです。彼女によると、SEL活動のほとんどは一日の最初の部分に組み込まれており、人間関係の構築、社会的プレッシャーへの対処、自分の長所と短所の認識などが含まれています。

10代の若者を対象にした最近の調査では、半年前に学校が大量に閉鎖された際、多くの若者がうつ病や不安、悲しみに苦しんでいたことがわかりました。約40%が、学校の大人から社会的、感情的なサポートを受けていないと答えました。

ワッツさんはVOAに、パンデミックに関連したストレスに加えて、毎日6時間をオンライン授業で過ごすことが、子どもたちにさらなるストレスを与えていると語っっています。そのため、バージニア州フェアファックス郡の教育者たちは”必死に”ストレス解消のための活動をまとめようとしているとワッツさんは言います。

教師も人間です

健康危機のため、不安やストレスの増大に直面しているのは学生だけではありません。

パンデミックが始まった後、イェール大学情動知能センターはCASELと提携し、教師を対象としたアンケートを実施しました。3日以内に5,000人以上の教師が回答し、不安、恐怖、心配、克服、悲しみの5つの感情を最も頻繁に感じていると答えています。中には、自分や家族がCOVID-19に感染するのではないかと心配している先生もいました。もう一つのストレスの原因は、自宅でフルタイムで仕事をしながら、自分や家族のニーズに対応しなければならないことでした。また、新しい教育技術を使うことへの不安もありました。

ワッツさんは、アーカンソー州のある学校の校長が、カウンセラーに教師のためのストレス解消のための活動を作るように依頼したことを指摘しています。そこでは、教師たちは新しいテクノロジーにまつわる問題に直面し、プレッシャーの増大に直面していました。また、パンデミックの影響で職を失った家族もいます。

アテンシアの高校も、現状の中でSELの価値を理解しているようです。彼は他の数人の教師に技術を教えることを任されています。

Teaching Social, Emotional Skills Critical in Pandemic

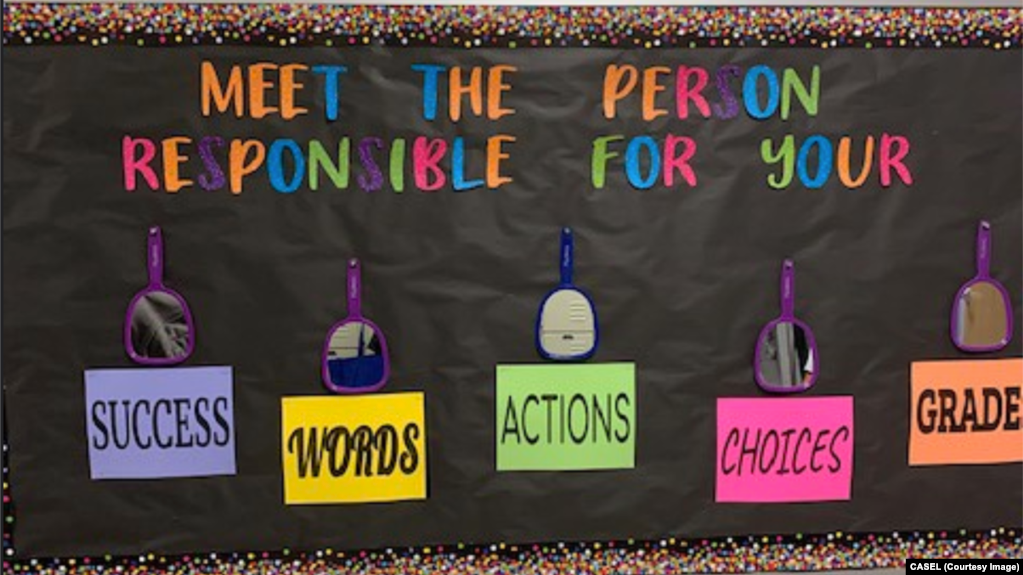

Bulletin board at Coretta Scott King Young Women's Leadership Academy in Atlanta

Bulletin board at Coretta Scott King Young Women's Leadership Academy in Atlanta

For Bryant Atencia, the social and emotional well-being of his students is more important than his lesson plans.

The coronavirus pandemic has affected students and their families in Laguna Province in the Philippines, where he teaches high school. Students are also facing what he calls a “huge adjustment” to distance learning.

Atencia told VOA that before the health crisis started, he mainly taught from books and gave tests on the material.

“But now, I try to touch the emotion, touch base with the students and their parents. I try to build up the relationship that would make the students more comfortable in taking lessons online.”

Right now, teachers around the world are amending their lesson plans for online learning. So, teaching social-emotional skills, or SEL, may not be high on their to-do list. Yet some experts say these skills are more critical than ever.

Hope floats

Christina Cipriano is director of research at the Yale Center for Emotional Intelligence at Yale University in Connecticut. In an open letter to teachers after schools closed in March, she wrote, “Now is when we need to apply everything we’ve learned about SEL.” She added that these are “real skills that can support us in managing the rollercoaster of emotions we will be having over the coming days and months.”

Atencia, who also trains teachers and teaches English at another job, was ready for whatever came. In May, he took online trainings on SEL and how to use it in the classroom.

One month before his high school students began classes, he held weekly Zoom video conference meetings with them. His goals were getting students excited about distance learning and identifying their skills and needs.

In one meeting, Atencia put the students into three separate online “rooms” and gave them a creative activity. He wanted to see how well they worked independently and in groups, and which ones would need the most support going forward.

The Collaborative for Academic, Social and Emotional Learning, or CASEL, is a research and training organization. It divides social-emotional skills into five areas. They are recognizing and controlling one’s emotions; setting and reaching positive goals; showing sympathy for other people; developing and keeping positive relationships; and making responsible decisions.

The Yale center’s research found that emotions like happiness and curiosity support a person’s ability to pay attention and have greater involvement in school. But emotions like anxiety and fear, especially over long periods, hurt one’s ability to think clearly.

Aileen Watts has witnessed this kind of anxiety in students firsthand.

In her 20 years of teaching, she has worked with students from all walks of life, including those who were homeless and those requiring special education. She has also taught Iraqi children living in the United States.

Watts says that, over the years, she has often included some form of SEL in her lessons.

Last year, she taught sixth graders at a school in McLean, Virginia. Some of the students were born in Iraq and had seen friends and family members killed.

Watts said she and other teachers built in activities to help students reduce anxiety. Classes took “brain breaks,” which meant stopping the lesson to play a short game or even do a dance. And, if a child was feeling anxious, he or she could partner with someone to help calm those emotions.

“We’ve discovered that if they’re stressed out, they don’t take in new information. They don’t participate.”

Watts, who is based in Arkansas, has just begun teaching fifth graders online at Fort Belvoir, a U.S. Army base in Virginia. She said most of the SEL activities are built into the first part of the day and involve relationship building, dealing with social pressure and recognizing one’s strengths and weaknesses.

A recent study of teenagers found that many struggled with depression, anxiety, and sadness during the mass school closures six months ago. Around 40 percent said they had not been offered any social or emotional support by an adult from their school.

Watts told VOA that in addition to pandemic-related stress, spending six hours in an online class daily causes children more stress. So, she says, educators in Fairfax County, Virginia are “desperately trying” to put together de-stressing activities.

Teachers are human, too

Students are not the only ones facing increased anxiety and stress because of the health crisis.

After the pandemic began, the Yale Center for Emotional Intelligence partnered with CASEL on a questionnaire for teachers. Within three days, more than 5,000 responded, saying they most often felt five emotions: anxious, fearful, worried, overcome and sad. Some teachers feared that they or a family member would get COVID-19. Another cause of stress was having to deal with their own needs and their families’ needs while working full-time from home. And there was anxiety around using new teaching technologies.

Watts noted that the head of one Arkansas school asked its counselors to create de-stressing activities for the teachers. There, the teachers were facing increased pressure from problems involving the new technology. And some have family members who have lost jobs during the pandemic.

_______________________________________________________________

Words in This Story

lesson - n. a single class or part of a course of instruction

adjustment - n. a change that makes it possible for a person to do better or work better in a new situation

comfortable - adj. causing no worries, difficulty or uncertainty

rollercoaster - n. a ride at an amusement park which is like a small, open train with tracks that are high off the ground and that have sharp curves and steep hills

positive - adj. hopeful or optimistic

curiosity - n. the desire to learn or know more about something or someone

anxiety - n. fear or nervousness about what might happen

participate - v. to take part in an activity or event with others

teenager - n. someone who is between 13 and 19 years old

desperately - adv. done in a way that uses all of your strength or energy and with little hope of succeeding